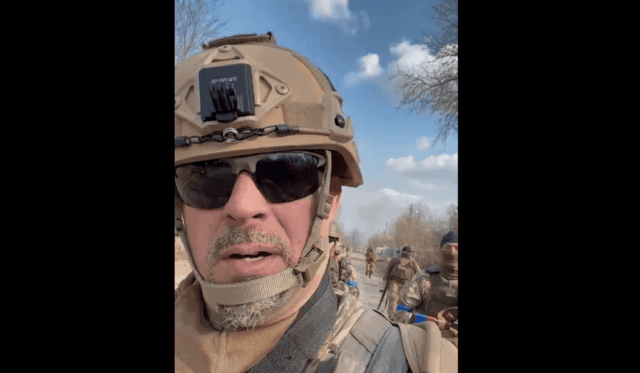

War in real time: TikTok and Twitter stars document Russia’s war in Ukraine Army veteran James Vasquez in Ukraine (Twitter screenshot)

A snowy sidewalk strewn with bloodied bodies. A beleaguered president roaming the streets of a country under attack. Missiles streaming. Sirens wailing. Teens making homemade bombs. And dead soldiers, so many of them, lying crumpled in fields and slumped in smoldering tanks.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has spawned a constant stream of online content, a deluge of audio-visuals that has countered Moscow’s disinformation campaign, spurred global leaders to action and helped, as they have in other recent conflicts in Syria and Ethiopia, change the way we see and understand war.

The bombings and violence in cities like Mariupol, Kharkiv and Kyiv feature a cast of newly minted stars — social media standouts who rely on satire, grit and an insider’s sensibilities to document the horrors for a global audience.

Ukranian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has become the most famous and tireless online presence with his riveting daily updates via the instant-messaging platform Telegram. But there are many others, including Illia Ponomarenko, a journalist who has garnered more than 1 million Twitter followers for his play-by-plays of military operations, and Vitali Klitschko, the mayor of Kyiv and a former heavyweight champion boxer who delivers dispatches from the aftermath of bombings.

They offer a quick-pulse stream of consciousness in a morality play where ancient brutality meets raw, digitized immediacy. They are influencers amid the ruins, defiant voices echoing from battlefields and bunkers.

Zelenskyy’s recent description of the relentless Russian siege of Mariupol as “a crime against humanity … happening in front of the eyes of the whole planet in real-time” seized upon what has separated the Ukraine conflict from many past wars: instantaneous documentation.

In February, even as Russia denied it was planning an attack, hints of the coming siege were registered on TikTok, where users posted hundreds of videos showing Russian military vehicles massing along the Ukrainian border.

On Telegram, Twitter and Instagram, Ukrainians have raised money for refugees, organized the exit of civilians from hard-hit regions and chronicled horrors, such as the March 10 bombing of a maternity hospital in Mariupol, where bleeding pregnant women were evacuated on stretchers.

The war in Vietnam was often referred to as the “first television war,” a technological advance from two World Wars decades earlier that had been recorded mostly through printed words and photographs. At the beginning of this century, the conflict in Iraq was still largely filtered to the outside world through journalists and documentary film crews.

The Arab Spring in 2011 was widely seen as the first revolutionary movement launched on social media. But the apps used then to spread uprisings — namely Twitter and Facebook — have evolved significantly in the years since, while new platforms more geared to sharing video have flourished. At the same time, the capabilities of the typical cellphone have expanded to the point where anyone can become an auteur.

Jane Lytvynenko, a senior research fellow at Harvard Kennedy’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, said social media have played a critical role in shaping the world’s reaction to Russia’s attack.

Instant communication “is having a direct effect on how Western countries are responding to the Feb. 24 invasion, and the reason why it’s having that effect is because regular people en masse are seeing what’s happening,” she said.

She compared the Ukraine war to the Soviet-era artificial famine imposed by Moscow on Ukraine in the 1930s, which killed more than 4 million people. “The facts of the genocidal famine did not get to Western audiences,” she said. “And so Ukraine was left to fend for itself.”

That is not the case today. While separating fact from fiction on social media isn’t always easy, there’s no question that the power and moral clarity of the many voices coming out of a once-peaceful nation of 44 million have made the crisis impossible to avoid. Some critics have argued that the social media feeds of white Europeans trapped in conflict have gained more attention than similar documentation of atrocities coming from Syria or African countries.

The drama of those in turmoil — as it has been since Homer’s “Iliad” — is compelling. Consider Klitschko, the boxer-turned-mayor, and the videos of him touring the sites of deadly strikes. Pacing around a rubble-filled Kyiv street in March, he pointed his cellphone camera at a destroyed apartment building, a bombed-out city bus and the crater where the munition hit. “These images (are) the truth,” he said in English. “That’s what Putin’s war looks like.”

Ponomarenko, a journalist with the Kyiv Independent who has been embedded with Ukrainian forces, has reported on the fighting with a mix of pain and awe. “One, two, three, four Russian tanks taken out,” he said in a recent clip as he panned across the smoking wreckage of militarized vehicles. “I call that a good day.”

On TikTok, young people have amassed huge followings for their simple explanations of what is happening in the war and their documentation of daily life in underground bomb shelters. One recent viral video showed a civilian carefully moving a land mine off a highway, a cigarette hanging from his lips.

And then there is Zelenskyy, a former comedic actor elected president in 2019 who is equal parts Jon Stewart and Winston Churchill. He seems to embody the spirit of the nation: exhausted, but still standing, and unrelenting in his demands that the West to do more to help Ukraine in what he has framed as a clear choice between good and evil.

His selfie-style videos lend a “social media authenticity that is pretty unimpeachable,” said Eugene Kotlyarenko, a filmmaker who was born in Ukraine.

“We live in an extremely media-sensitive moment where people are very tuned into cues of authenticity,” Kotlyarenko said. “Zelenskyy seems really earnest and kind of vulnerable but simultaneously strong.”

The president’s dispatches, which he posts every few hours on Telegram, are part of a larger world of Ukrainian content that has helped counter Russia’s widespread disinformation campaign, experts say.

Just like it did in the United States to try to influence the 2016 presidential election, Russia has pushed fake news about its war on Ukraine in an effort to sow confusion.

It has circulated claims that Ukraine is ruled by neo-Nazis and that the U.S. is developing chemical and biological weapons in Ukraine to use against Russian troops. It has charged that the pregnant women bombed at the maternity ward in Mariupol were actually crisis actors. “Very realistic make-up,” the Russian Embassy to the U.K. wrote in a Twitter post that was later deleted.

“They’re creating a few different narratives, and they don’t particularly care which one sticks,” said Lytvynenko. “The goal is to cloud people’s thinking about the war, to make it seem like it’s too complicated for them to understand so that they tune out or change the conversation.”

At home, Russia hasn’t even acknowledged a war is taking place, deeming its military assault on Ukraine a “special operation,” and threatening anybody who says otherwise with prison.

The adage that truth is the first casualty of war is also playing out on many platforms across cyberspace.

In the war’s early days, Facebook Gaming featured videos presented as live footage of attacks on Ukraine that turned out to be from a military video game. On TikTok, many accounts featured an audio clip of Ukrainian soldiers cursing at a Russian warship that has asked them to surrender — with text saying the soldiers had died. They lived.

“It is difficult — even for seasoned journalists and researchers — to discern truth from rumor, parody and fabrication,” according to a report from Harvard researchers who studied TikTok’s impact on the war.

Aware of such manipulation, the Biden administration recently invited several prominent TikTok producers to a briefing on the war, in hopes that they would help push accurate information. “We recognize this is a critically important avenue in the way the American public is finding out about the latest, so we wanted to make sure you had the latest information from an authoritative source,” one official said, according to a recording of the meeting obtained by the Washington Post.

But disinformation continues to spread.

A few weeks ago, a manipulated video circulated in which Zelenskyy appeared to ask his soldiers to lay down their arms. Zelenskyy quickly took to Telegram to denounce it. A few days later, a different fake video popped up, in which Russian President Vladimir Putin announced peace with Ukraine.

The war, of course, carried on, both on the battlefield and online.

___

© 2022 Los Angeles Times Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC