New movie reveals elite Air Force unit’s secret battles against enemy supply networks during Vietnam War An F-100f Super Saber. (The Misty Experiment photo/Released)

A new documentary, out May 2, tells the story of a group of 157 U.S. Air Force fighter pilots that formed an experimental unit to disrupt the flow of weapons into South Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

In 1967, as weapons and supplies flowed freely down from North Vietnam to South Vietnam, a group of experienced fighter pilots volunteered to form a top-secret unit with the code-name “Misty.” The job of this Misty unit, over the course of three years, was to fly fast and low over the North Vietnamese supply lines and identify targets for aerial strikes, disrupting the flow of weapons to the war in South Vietnam. The story of this experimental unit, and their highly dangerous mission, is retold through the documentary film “The Misty Experiment.”

The Misty Experiment (Trailer) | Film from Floor 1 Productions LLC on Vimeo.

“The Misty Experiment” was the product of years of interviews with more than 20 members of the legendary unit and is set to air on PBS channels on May 2.

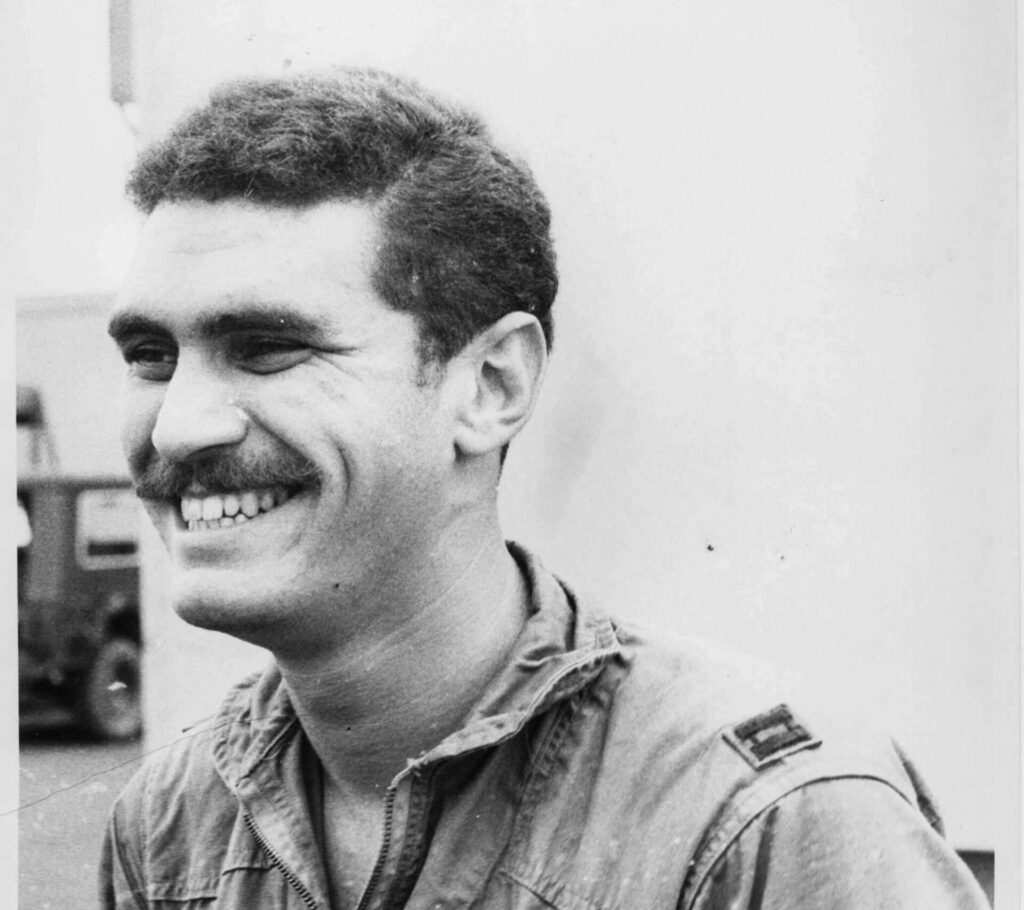

Doug Echenberg, who served as an Air Force flight surgeon for the experimental unit, spoke with American Military News about his Vietnam war experience.

“I got to see the entire Misty operation and I got to know maybe 100 pilots who passed through Misty,” said Echenberg, who was one of the Misty members interviewed in the film and who helped complete the film’s production.

Early on in the Vietnam War, airborne forward air controllers (FACs) worked to spot targets for the Air Force using slow, propeller-driven aircraft. This particular military doctrine proved particularly dangerous for countering the flow of supplies in the border region between North and South Vietnam, where the North Vietnamese forces had gathered a high concentration of anti-aircraft weapons to protect their supply lines.

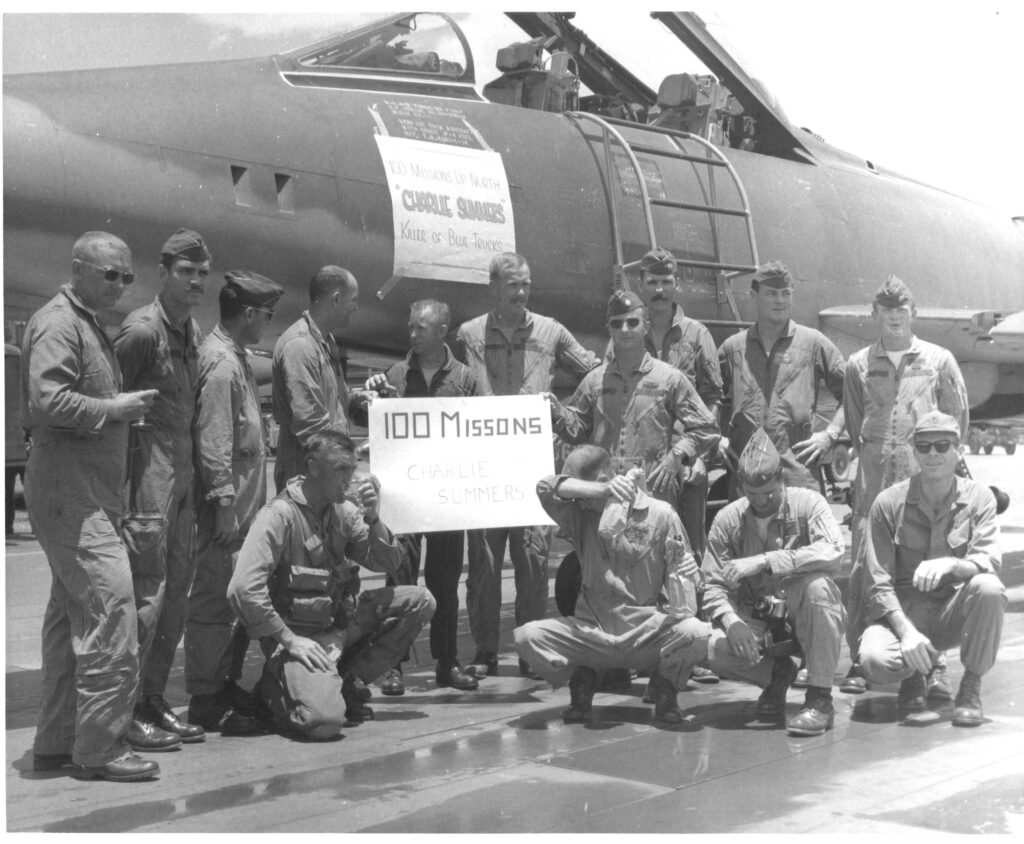

The Mistys, which were created from a flight of the 416th Fighter Squadron, were formed in June of 1967 to try out a new forward air controller concept to stop the flow of enemy troops and supplies while avoiding some of the dangerous anti-aircraft fire. Their new concept entailed using special two-seat F-100F Super Saber fighter jets as so-called “Fast FACs,” flying much faster than their propeller-powered counterparts. These Misty Fast FACs would fly at high speeds, constantly jinking and turning in irregular patterns to make themselves difficult for North Vietnamese anti-aircraft weapons to track and shoot down, all while they looked for and marked enemy targets.

“It was a very high-G, constant movement of the aircraft so no one could get a bead on you,” Echenberg told American Military News.

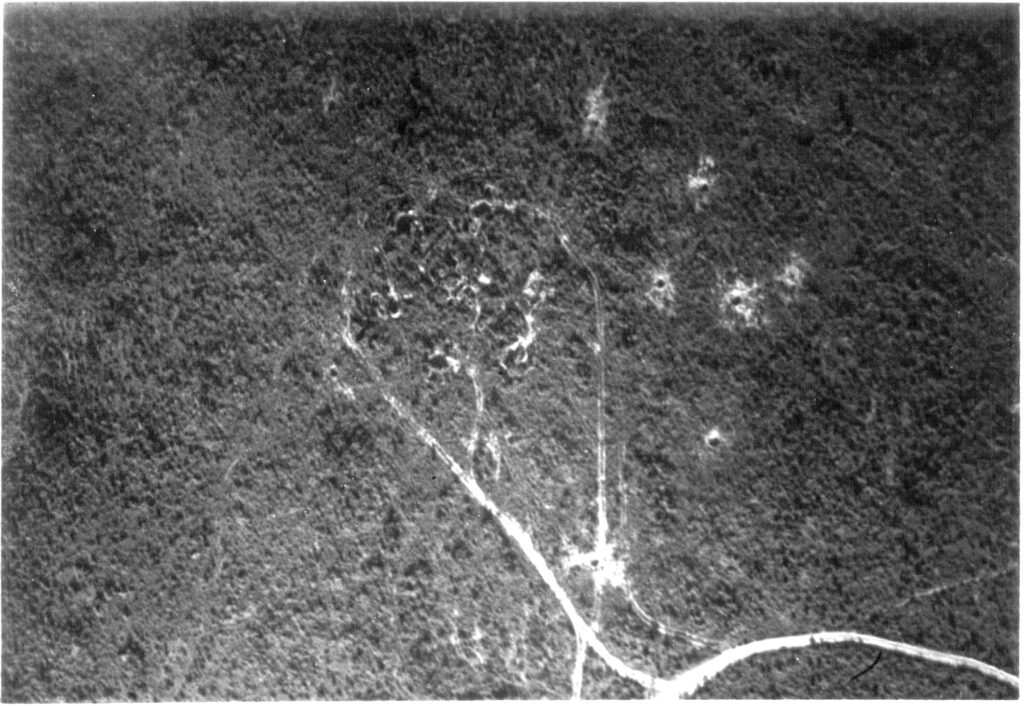

As they flew fast and low over North Vietnam, the Misty crews would take photos to try to find potential targets. Back at their base, the Misty pilots would study the photos to map out the movements of the North Vietnamese. The Misty’s quickly learned to pick out the enemy supply routes and their anti-aircraft weapons, even when they were well hidden by the dense jungle canopy.

The Misty Fast FACs would also dive-bomb those enemy targets, shooting at them with smoke-filled rockets to mark their positions for Air Force attack aircraft and bombers to strike.

While this “Fast FAC” approach to spotting and marking targets was more effective than the slow-moving propeller aircraft other FACs used, the mission of the Mistys was still incredibly dangerous. Of the 157 Misty pilots who served over a three-year time span, 34 were shot down, some multiple times. The Misty pilots were told at one point, that they were facing the largest concentration of anti-aircraft weaponry fielded since World War II.

“We had a high shoot-down rate,” Echenberg said. “But the impact didn’t really strike me until many years later about how dangerous it was and how different it was.”

With the challenging nature of the mission, the volunteers for the Misty unit still had to go through a rigorous selection process. The unit’s high level of professionalism is reflected in part by its military decorations, including a Medal of Honor. Misty pilot George Everette “Bud” Day received the highest individual U.S. military decoration for defying his captors after being shot down over North Vietnam. Despite being badly injured and immediately captured, Day escaped and attempted to get back to South Vietnam before being recaptured once again. At a prison in Hanoi, Day continued to provide his captors with false information, in order to protect the lives of his fellow aviators.

Other Misty pilots had professional success following the war. The unit produced seven generals, two Air Force Chiefs of Staff, two NASA astronauts and numerous successful business executives.

Retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Donald Shepperd, who served as the director of the Air National Guard after his time with the Mistys, said the experience with the experimental Vietnam War-era unit mostly taught him the importance of making sure the force had the right tools and training for the job they were doing.

Shepperd said the task the Mistys took one was nearly impossible. Rather than striking enemy weapons and supplies at their source in North Vietnam, the Misty pilots had to disrupt them as they were already proliferating across the border with South Vietnam. The Misty pilots of the 416th Fighter Squadron were trained earlier on in the Cold War as a low-level nuclear fighter bomber squadron and the F-100fs they flew in during the Vietnam War were repurposed trainer aircraft.

“We did not have the equipment we needed,” Shepperd said of the Misty unit. “. . . We had no radar warning gear. We had no ‘chaff’ that would deflect [Surface to Air Missiles] . . . We had no standoff weapons such as we have today. We had no night capabilities.”

From that experience, Shepperd decided that as a leader, “I’m never going to let the people underneath me go to a war for which they are not trained, with equipment that is not suitable for the war, if I can do anything about it.”

Despite the mismatched training and equipment for their mission, the Misty pilots made due and, as Shepperd put it, “We did make a difference and we basically slowed them down, we attacked a lot of targets that needed to be attacked, we blew up a lot of things in the way of people and munitions and vehicles that would have attacked our kids and the south and killed them.”

The effort to produce “The Misty Experiment” became a labor of love for the Mistys. Filmmaker Danny L. McGuire filmed most of the interviews with the Misty pilots several years ago and created the template for the film, but was unable to complete the project due to health problems. The film’s production was paused for several years before Echenberg took over the effort and reached out to his grandson, award-winning filmmaker Ian Adelson, to complete the project.

Adelson said it was an incredible experience getting to help tell a piece of his family’s history.

“To be able to get firsthand accounts from the pilots themselves . . . was really eye-opening and enlightening for me,” said Adelson, whose production company Floor 1 Productions completed the film. “And then getting to work with my grandfather was such a fun experience. It sort of opened up this whole other conversation that we started having about his history and what his experiences were.”

Echenberg noted McGuire “really immersed himself” in the unit when he was first starting on the project and had gotten to know the Misty pilots well over the years. “And that’s why I think the movie is so accurate.”