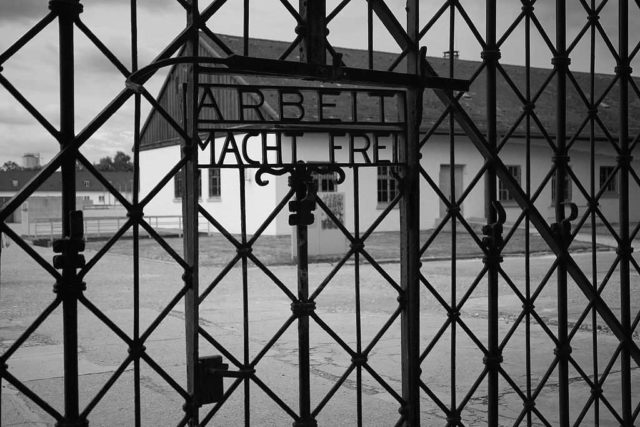

Nothing could prepare Black World War II veteran for horrors witnessed at Nazi concentration camp Dachau Concentration Camp. (Rennett Stowe/WikiCommons)

Middlesex County Prosecutor’s Office Bias/Community Outreach Unit Agent Reggie Johnson tells the story of his father, U.S. Army Maj. George Yancy Johnson, who endured racism and witnessed horrific acts of inhumanity while serving during World War II.

Reggie Johnson said his father was one of only a few Black commissioned officers at the beginning of World War II, and took part in the liberation of the Dachau Concentration Camp.

“I’d heard of (the camp), but nothing could prepare me for the reality of what humans could do to each other,” George Johnson wrote in his diary. “I eventually saw Grafenwoehr and Buchenwald, but Dachau was my first.”

To commemorate Holocaust Remembrance Day, the Jewish Federation in the Heart of New Jersey and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Metuchen-Edison co-sponsored a recent virtual presentation where Reggie Johnson spoke about his father’s military experiences and how his father influenced his career choices.

“Due to challenges my father faced both in the military and as a civilian, I decided to join the NAACP to secure political, educational, social and economic equality of rights in order to eliminate race-based discrimination and ensure the health and well-being of all persons,” Reggie Johnson, a lifelong Metuchen resident, said.

George Johnson was born on May 21, 1919, in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, and completed 12 years of education at Greensburg High School. He enlisted in the Scots Fusiliers of Canada’s 54th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment in the winter of 1940.

His father’s decision to enlist was strictly financial, Reggie Johnson said, because of the limited career options available to him, including bellhop, brick maker, butler or working in the coal mines.

“The Canadian Air Force discriminated against Blacks joining their unit, however the Canadian Army waived that policy during wartime and accepted Blacks, or at least my father was,” Reggie Johnson said.

On Sept. 28, 1945, George Johnson left the Canadian Air Force and enlisted in the U.S. Army.

“My father entered the war before Black Americans were allowed to enlist. Since he enlisted in the Canadian Army, he immediately experienced combat and was wounded on the battlefield. Due to my father having combat experience, the U.S. Army promoted him to a sergeant,” Reggie Johnson said.

One-and-a-half million Black Americans joined the military during World War II. Of that number, 125,000 saw active duty and 708 died during combat.

First stationed in Fort Meade, Maryland, George Johnson joined a Black regiment that included doctors, lawyers and teachers who were tasked with pouring old crank case oil around the base perimeter to get rid of the mosquitoes.

“My father’s first sergeant was white and illiterate,” Reggie Johnson said. “My father would help him read the roll call list. Fortunately, he could memorize it, like a parrot. One day he tried to read the roll call list unsuccessfully on his own, and my father told him with a straight face that he was reading it upside down.

“The privilege of being a white officer was to command a regiment consisting of better educated Black troops,” he added.

In August of 1945, George Johnson was stationed in Germany and was assigned to the Dachau concentration camp,the first and longest-running Nazi concentration camp.

Detailing what his father witnessed at Dachau, Reggie Johnson read a passage his father wrote in his diary.

“Some people tried to deny Dachau and the other concentration camps, but that’s like denying that the Army in the 1940s was Jim Crow or that Blacks in the south got lynched. I know what happened,” George Johnson wrote. “The odor of death still haunts my dreams 60 years later. I got there at the tail end of when they were dropping the cyanide-based pesticide pellets.

“Driving to Dachau, you could smell the stench about five miles before you got there. The stench was horrible.”

George Johnson wrote how he and his fellow soldiers were in disbelief when the villagers swore that they didn’t know what was going on.

“We guarded a German town and could see the crematoriums from their square,” he wrote. “Some say at night when the crematoriums worked full time on their task of death, the whole area used to light up as though morning came.

“The railroad tracks went right by the town. When boxcars carrying Jewish prisoners rolled past, villagers had to hear the screams and hollers.”

When Gen. Dwight Eisenhower visited the camp, George Johnson said he ordered roadblocks around the village, and he insisted the civilian population see the inside of the Nazi concentration camp by having them clean it.

“Before the Americans liberated Dachau on April 29, 1945, there were 67,665 prisoners in the camp, and before our forces got there, the Nazis forced thousands of prisoners on a death march and stowed away the dead and dying,” George Johnson wrote. “I later saw the 30 railroad cars filled with bodies and like my fellow soldiers, dealt with the pain that lingers in me to this day.”

George Johnson wrote the Nazis had divided the camp into areas for the different groups of people being held there.

“The barbed wire fence looked like the devil’s arms encircling the camp,” he wrote. “It separated the camp from the crematoriums and gas buildings. The trees and the ditches concealed the crematoriums from the prisoners, but we felt them anyway, knowing what happened.

“I imagined the last moments of the men, women, and children the Nazis stripped nude and forced into the death showers. I felt the despair and the gas cling to me as we left the building. Smoke still hung in the air; I could taste it. The bodies like cordwood lined the fields behind the barracks.”

George Johnson wrote about seeing a woman, who looked about his mother’s age, with her ribs sticking out. “There were so many bodies the GIs couldn’t bury them fast enough and still treat them with the respect they’d been denied in life,” he wrote.

He also wrote about he and fellow soldiers removing a desk from the second floor of a barracks, the drawer opening and pelting them with what felt like bullets or hailstones.

“We gasped,” George Johnson wrote. “They were the fillings of teeth, silver and gold fillings the commandant had kept in his private stash. I couldn’t wait to finish my assignment. I would never be the same.”

Reggie Johnson said after the war, his father continued to serve in the U.S. Army and throughout his military career he was stationed in Canada, England, Germany, Korea and France.

Despite being an officer, his father wrote about the difficulties traveling from one base to another in the 1950s, by way of Route 66, because of Jim Crow laws banning Black people from using roadside hotels, bathrooms, restaurants and gas stations.

“Even with my father dressed in his military uniform, we still were denied service,” Reggie Johnson said. “We had the Green Book and would stop at train stations to meet the Black porters to ask them about area restaurants, but we spent most evenings sleeping in our Studebaker automobile.”

George Johnson retired from the U.S. Army on July 31, 1962, and received several medals, including the Korean Service Medal with seven Bronze Stars, the United Nations Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Armed Forces Reserve Medal and Army Occupation Medal.

“While the GI Bill’s language did not specifically exclude African-American veterans from its benefits, it was structured in a way that ultimately shut doors for the 1.2 million Black veterans who had bravely served their country during World War II, in segregated ranks,” Reggie Johnson said. “In fact, the wide disparity in the bill’s implementation ended up helping drive growing gaps in wealth, education, and civil rights between white and Black Americans.”

Today, Reggie Johnson is responsible for investigating bias-related incidents in Middlesex County, as well as providing training to municipal police officers and leading community outreach programs. The work, he said, helps build bridges between communities to combat racism and hate by focusing on what people have in common, shared experiences and how they have worked together in the past.

___

© 2022 Advance Local Media LLC

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.